Ontology, Epistemology and Axiology

Ontologically, learning is important for the discovery, communication, refinement, and understanding of personal and collective identities. As individuals who perceive the world through unique filters related to culture, religion, socio-economic status, government structure, language, biology, lived experience etcetera, it becomes increasingly relevant that we reflexively inquire about who we are. Personality traits, interests, aptitudes, dislikes, sexual orientation, cultural values, political ideals, metaphysical beliefs, or religious preference to name a few. The importance of these things, and many others, enable us to situate ourselves collectively within humanity or carve out a new position. Therefore, learning must permit the discovery and continual refinement of personal identity while enabling the communication of that identity, or the understanding of identities external to us.

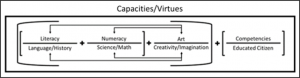

Epistemologically we require the tools necessary for exploration and participation in the world inside and external to us. Literacy (language and history), numeracy (science and mathematics), art (creativity and imagination), and competencies (educated citizen) contain the crucial knowledge required for such exploration (BC’s New Curriculum, n.d.). Depending on innate predispositions some subjects may prove more valuable than others, but they all must be approached while developing core capacities or virtues.

Figure 1

Diagram of epistemological beliefs

As Figure 1 demonstrates, first we consider the development of literacy and numeracy. Literacy consisting first of language empowers students to begin communicating and defining internal relationships externally (emotions and quality). Numeracy while paralleling literal development allows students to then begin exploring relationships of external objects such as quantity and value and thus beginning critical thinking and problem-solving processes. Art is secondary only to literacy and numeracy in this model because creativity and imagination are constantly interacting with literacy and numeracy (language, history, science, mathematics) as learning reaches deeper levels. The interactions of these three topics enable the formal introduction of already parallel developing competencies and societal values concerning an educated citizen (BC’s New Curriculum, n.d.). Competencies and attributes of an educated citizen may be flexible within any given society, culture, generation etcetera but generally they are the skills needed for someone to survive, strive, and participate in the world.

Social and emotional well-being are considered outside to while containing all other learning because they are the most important. The capacities and virtues (social and emotional) factors of learning are developed within and throughout every other subject and interaction. Buber (1947/2002, 1948, 1958/2000, 1965) and Aristotle (2000) as cited in Bai et al. (2015) indicate a list of seven capacities or virtues that are necessary to dialogue or interact successfully in the world:

“…Becoming aware…[,]…confirmation of other…[,]…inclusion or empathy…[,]…presence…[,]…willingness and ability to explore the unknown and different…[,]…ability to cognize and grapple with paradox…[,]…ability to synthesize what is being perceived….”

There are always uncontrollable variables when considering social and emotional development and regulation. However, within a framework of interculturalism these core capacities and virtues help us to explore and uphold the importance of reaching social and emotional maturity, as well as lay the foundation for positively interacting with our internal identity and those external to us (Bai et al., 2015). In this way we can begin to affect change at an individual level to increase our capacity to dialogue, identify and unite with people that we may otherwise struggle to understand because of dramatic differences in identity (Verkuyten et al., 2018).

Axiologically, it is obvious that every member of a society, regardless of race, religion, culture, socio-economic status, ability, sexual orientation etcetera should be represented in learning. This holds especially true for a multi-cultural country like Canada and the pedagogical interculturalism that the previous ontology and epistemologies indicate (Bai et al. 2015; Verkuyten et al., 2018; Robson, 2013). Furthermore, as Canada exists as a nation of settlers, the recognition and implementation of indigenous ways of knowing and being, consistent with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Calls to Action, becomes extremely valuable to promote dialogue, unity and identity between and for all nations and peoples (First Nations Education Steering Committee, n.d.; Robson, 2013; Verkuyten et al., 2018). This axiological importance is reinforced further through decolonization and indigenization of curriculum in British Columbia and demonstrated through BC’s new curriculum, First Peoples Principles of Learning and outlined in BC’s Professional Standards and the B.C. Teachers’ Federation’s Ethical Code of Conduct (BC’s New Curriculum, n.d.; First Nations Education Steering Committee, n.d.; Government of British Columbia, n.d.; British Columbia Teachers’ Federation, 2020). Truthfully, we all want to experience success and triumph, happiness and freedom, safety and acceptance.

Pedagogical Philosophy

Operant conditioning, bells and dogs, reinforcement, extinction, stimulus discrimination, unconditioned responses, behavior modification, and Pavlov (1927) and Skinner (1938) at the core (Cohen, 1999; Lindsay et al., 2008). The classic approaches to manipulate the world and empty feeling it leaves when your life is all effect because you lack willful cause. This was my bread and butter as a psychology major. It was simple, effective, and cut out all the fluffy while talking about cognition.

Jungian introverts, extroverts, the eight core personality traits, libido, collective unconscious, self, ego, and archetypes (Cohen, 1999; McLeod, 2018). Personality. The nurture questions that behaviorists cannot talk about. The freedom we have and the connections we have to each other. I jump on board with Carl Jung (1948 as cited in McLeod, 2018) while he elaborated on his theories of introversion and extroversion, he even had me while he spoke about ancestral memory, then I lost touch because my behavioral nature kicked in. Carl, this is good stuff, but how do we measure it?

Adler and Maslow captured my attention immediately (McLeod, 2020; Lindsay et al., 2008). I experienced a mental break in my third year of psychology because these two guys understood me. So much so, that if two guys I never met could explain the reason why I was the person I was, what about the rest of the world? Was I that transparent? Maybe it was scary because I was studying physiology of motivation and emotion concurrently. Either way, must have nearly killed my ego because I began to change my behaviorist beat. Motivation and emotion were where my heart was and remains. Although there is still a small feisty behaviorist in me today, effects began to slowly lose importance as I was exposed to the real mind programmer. Affective emotion. Learning can happen effectually, but only emotion can do it in one try and embed it forever.

Motivation was tougher to tease out while considering neurotransmitters, receptors, reuptake, excitation, and inhibition. Consequently, I neglected to consider motivation until I had children of my own and began studying education. To that end, I confronted a world filled with dichotomies. Right or wrong, love or hate, good or bad, black or white, light or dark, science or art? I see this within my two stepchildren. They focus on dichotomy. They want to know what they are by contrasting what they are not, then look to me for confirmation and validation. In this way, any authority in a child’s life easily and unknowingly fills them with dichotomies, and they regurgitate conditions of worth. Personally, I hate conditions of worth because my childhood was filled with them and I still bear the emotional scars. You are worthy, I am proud, I do love you, you are brilliant. It is that simple. As an authority in my home and future classroom, there are only two questions I care about. What do you like doing and how can I help? Afterall, we are the educators, and they are the students. I received professional training therefore I am accountable and responsible for fitting students with the correct curriculum, not fitting curriculum with the correct students.

With a history of cognition and behaviorism, constructivist theorists like Vygotsky and his zone of proximal development and scaffolding will enable me to fit students with the correct curriculum structure while developing valuable social and collaborative skills (Kurt, 2020). However, that is not to say that I would not use behaviorist theory in class to reinforce appropriate behavior or work in some kind of token economy (Lindsay et al., 2008) Considering the impact Jung, Adler and Maslow had on my life, humanist perspectives will reflect in my instruction because I consider the freedom of individuality sacred (Cohen, 1999; McLeod, 2020; Lindsay et al., 2008). More specifically, I see the value of interpreting student motivation through a hierarchy of needs and therefore digging deeper into student performance as a reflection of something either they or myself are missing to reach deeper levels of learning (Lindsay et al., 2008). Although a social re-constructivist approach will help elucidate student agency and promote conversation and confidence within my classroom, my use of such theory will mirror my interest in developing interculturalist capacities and virtues in students (Bai et al., 2015; Beaudrie et al., 2015; McGregor, 2019; Verkuyten et al., 2018). In this way I hope to appeal to affective emotion and guide students through the necessity of reaching significant emotional intelligence. In other words, the height humanity could reach if society knew how “to know, to love and to heal – all in one. [Without forgetting] it knows as much as it loves and heals. It loves, only if it truly knows and heals. [And] it heals if it loves and knows…” (Panikkar, 1992 as cited in Bai et al., 2015). Through these words and my gift as an intercessor I hope to promote the joining of multicultural and interculturalist values to achieve social and emotional growth and change within the classroom and beyond

References

Aristotle. (2000). Nicomachean ethics (R. Crisp, Trans.). New York: Cambridge University Press

Bai, H., Eppert, C., Scott, C., Tait, C., Nguyen, T. (2015). Towards Intercultural Philosophy of

Education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 34(6), 635-649. doi:10.1007/s11217-014-9444-1

BC’s New Curriculum. (n.d.) Curriculum Overview. Retrieved October 5, 2020, from

https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/overview

British Columbia Teachers’ Federation. (2020). Professional Rights and Responsibilities.

Retrieved November 2, 2020, from https://bctf.ca/ProfessionalResponsibility.aspx

Beaudrie, J., Murrell, K., Nelson, J., Seidel, M., Shelton, V., South, O. (June 30, 2015).

Educational Philosophies. https://graduatefoundationsmoduleela.wordpress.com/social -reconstructionism/

Buber, M. (1948). Israel and the world: Essays in a time of crisis. New York. Schocken Books.

Buber, M. (1965). The knowledge of man: Selected essays. (R. Smith & M. Friedman, Trans.).

New York: Harper & Row

Buber, M. (2000). I and thou. (R. Smith, Trans.). New York: Scribner. (Original work

published 1958)

Buber, M. (2002). Between man and man. (R. Smith, Trans.). London: Routledge. (Original work

published 1947)

Cohen, L. M. (1999). Section III: Philosophy of Education. Module One: History and Philosophy of

Education. https://oregonstate.edu/instruct/ed416/module1.html

Dixson, D. D., Worrell, F. C. (2016). Formative and Summative Assessment in the Classroom.

Theory Into Practice, 55: 153-159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1148989

First Nations Education Steering Committee. (n.d.). Learning First Peoples Classroom Resources.

Retrieved September 17, 2020, from http://www.fnesc.ca/learningfirstpeoples/

Government of British Columbia. (n.d.). Standards for B.C. Educators. Retrieved November 2,

2020, from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/k-12/teach/standards-for-educators

Jung, C. G. (1948). The phenomenology of the spirit in fairy tales. The Archetypes and the

Collective Unconscious, 9(Part 1), 207-254.

Kurt, S. (July 11, 2020). Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding. Educational

Technology. https://educationaltechnology.net/vygotskys-zone-of-proximal-development-and-scaffolding/

Lindsay, D. S., Paulhus, D. L., Nairne, J. S. (2008). Learning: Conditioning and Observation. In

Nelson (Ed.), Psychology: The Adaptive Mind (3rd ed., pp. 218-257. Thomson Nelson.

McGregor, S. (2019). Education for sustainable consumption: A social reconstructivism model.

Canadian Journal of Education, 42(3), 745-766.

McLeod, S. (May 21, 2018). Carl Jung. Simply Psychology.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/carl-jung.html

McLeod, S. A. (March 20, 2020). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychology.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

Panikkar, R. (1992). A nonary of priorities. In J. Ogilyvy (Ed.). Revisioning Philosophy (pp. 235-

236). New York: State University of New York Press.

Pavlov, I. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the

cerebral cortex. (trans. and ed. G. V. Anrep). New York: Oxford University Press.

Robson, K. L. (2013). Sociology of Education in Canada. Pearson Canada Inc.

Skinner, B.F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-

Century.

Verkuyten, M., Yogeeswaran, K., Mepham, K., Sprong, S. (2018). Interculturalism: A new

diversity ideology with interrelated components of dialogue, unity and identity

flexibility. European Journal of Social Psychology. 50: 505-519.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2628

Leave a Reply